创新背景

早衰症是一种导致儿童快速衰老的遗传疾病,这种基因综合症会导致人类过早衰老——携带早衰症突变基因的儿童智力正常,但出现普遍衰老的早期迹象,包括脱发和听力下降。到了青少年时期,他们就显得很老了,很少有人能活过13岁。

创新过程

通过“碱基编辑”,研究人员治愈了老鼠的早衰症,一组美国研究人员在《自然》(Nature)杂志上发表了一篇论文,这是基因疗法的一个里程碑。

美国国立卫生研究院院长弗朗西斯·柯林斯(Francis Collins)与哈佛大学教授大卫·刘(David Liu)等人合作,共同应对早衰症。

这一在小鼠身上成功测试的成就,是由刘发明的被称为“碱基编辑”的第二代CRISPR基因编辑技术而成为可能的。有了这个,研究人员可能最终能够纠正包括早衰症在内的人类终身遗传疾病。

一种罕见但有毁灭性的疾病

人类基因组计划(Human Genome Project)的前负责人弗朗西斯·柯林斯(Francis Collins)在取得这一突破之前已经研究早衰症很多年了。

2003年,柯林斯的实验室发现早衰症是由一种基因的突变(可以把它看作是“拼写错误”)引起的,该基因编码一种名为Lamin a的蛋白质。Lamin a在细胞核中起着结构性作用。

许多人在各种基因中都有突变,但由于人们通常有两个基因副本(一个来自母亲,一个来自父亲),则倾向于至少有一个好的副本,这通常就足够了。

但Lamin A中的早衰症突变是不同的。虽然可能存在一个好的拷贝,但突变的拷贝会产生一个有毒的产品,把事情搞砸,就像一个扳手在破坏。这种类型的突变被称为“显性负突变”。

理想的解决方案是使用CRISPR专门纠正突变副本。有了这个基因编辑工具,科学家们可以将一把分子“剪刀”对准基因组(DNA)的任何部分。不幸的是,第一代CRISPR技术虽然擅长切割基因,但却没有纠正Lamin A突变所需的外科手术精度或效率。

大量细胞编辑的并发症

CRISPR剪刀擅长于找到目标并进行切割,但之后的重建手术留给了细胞,而且不能保证每个细胞都能进行。

在实验室里,研究人员通常可以通过在培养皿中培养一些细胞进行进一步研究之前纠正它们。

但在人类中,我们需要准确地纠正大多数细胞,如果不是全部的话。在病人手指的五个细胞中纠正早衰症突变,而让身体的其他部分得不到修复,这是毫无意义的。

这就是David Liu关于“基础编辑器”的工作至关重要的地方。Liu很早就发现了CRISPR技术的局限性,并开始开发分子机器,它可以做更多的工作,而不仅仅是作为靶向分子剪刀。他从自然产生的酶开始研究,这种酶可以将遗传密码的一种化学基础转变为另一种;例如,可以将A(腺嘌呤)转化为G(鸟嘌呤)或C(胞嘧啶)转化为T(胸腺嘧啶)的酶。

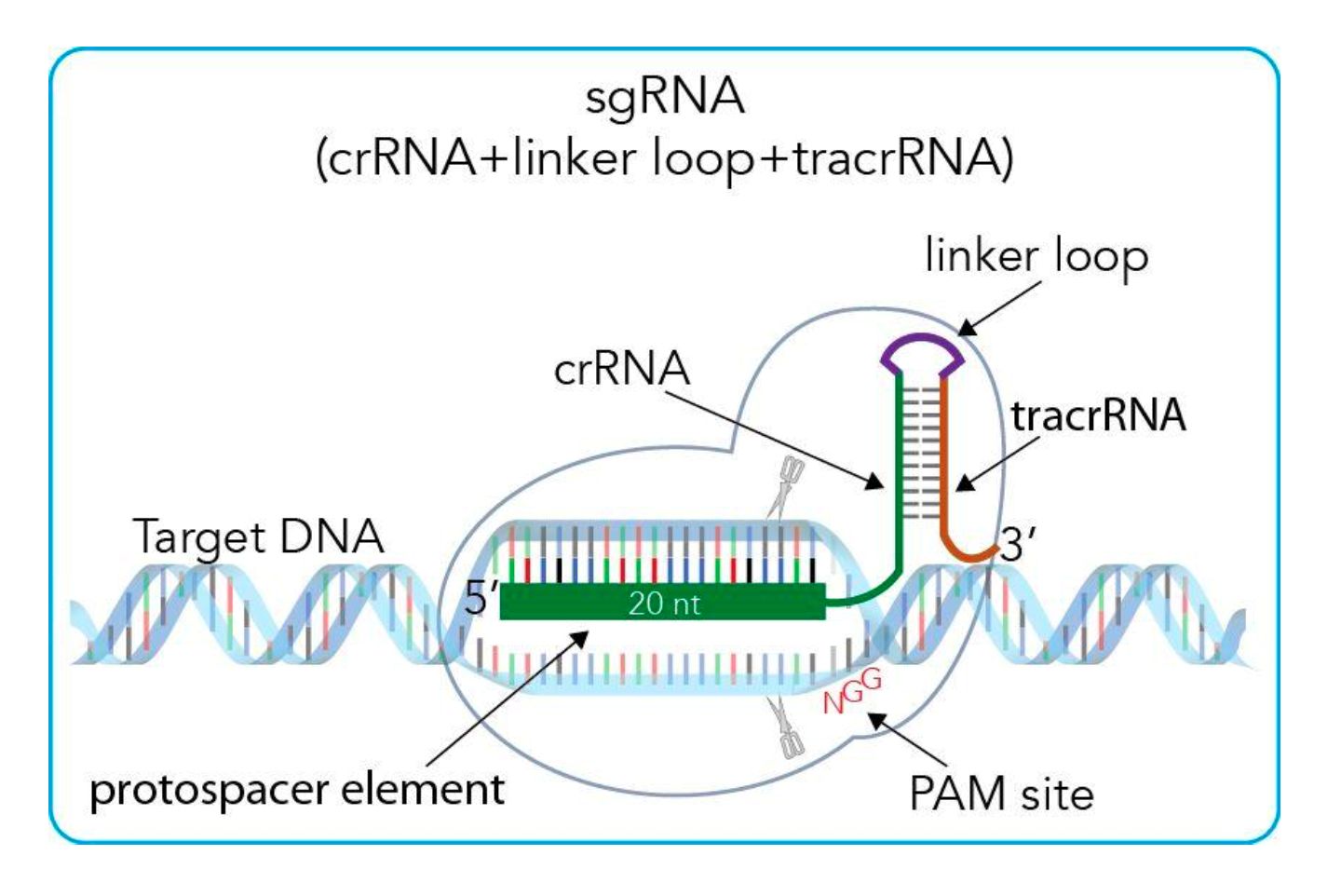

DNA的双螺旋形状是由糖-磷交替的主干(两侧)支撑的。每个糖的骨架上都附着着四种化学碱基中的一种:腺嘌呤(A)、胸腺嘧啶(T)、鸟嘌呤(G)和胞嘧啶(C)。这些碱基的顺序决定了生物体的遗传密码。在上面

然后,Liu对酶进行了修改,使其更精确,并将它们融合到CRISPR中,创造出被称为“碱基编辑器”的融合蛋白。由于CRISPR技术擅长读取DNA并找到目标,它可以有效地将编辑器传递到需要改变的基因上。

值得强调的是,Liu有意开发了碱基编辑器,使它们可以改变字母,但不再像CRISPR剪刀那样切断DNA。这是至关重要的,因为切割DNA增加了更大的染色体缺失的风险,这可能会损害细胞。

Collins、Liu和他们的同事们知道,他们必须将碱基编辑器植入患有早衰症的老鼠的所有(或至少大部分)细胞中,才能治愈它。为此,他们使用掏空的病毒作为传递载体。

他们使用了基于腺相关病毒(AAV)的载体,因为它是最小的病毒之一,不会导致任何已知的疾病。Collins和Liu将AAV病毒粒子与编码相关碱基编辑酶的基因打包,并将其注入小鼠体内。接受治疗的老鼠基本上避免了疾病,变得与健康的老鼠难以区分。

创新关键点

研究人员开发分子机器——它能做更多的工作,而不仅仅是作为靶向分子剪刀。他从自然产生的酶开始研究,这种酶可以将遗传密码的一种化学基础转变为另一种;例如,可以将A(腺嘌呤)转化为G(鸟嘌呤)或C(胞嘧啶)转化为T(胸腺嘧啶)的酶。

然后,Liu对酶进行了修改,使其更精确,并将它们融合到CRISPR中,创造出被称为“碱基编辑器”的融合蛋白。

创新价值

碱基编辑CRISPR工具致力于让基因治疗的专家和受早衰症等疾病困扰的家庭的梦想成真。这方面的工作才刚刚开始,但它提供了新希望,这是基因疗法的一个里程碑。

Progeria may be treated with the new CRISPR technology

Using "base editing," researchers have cured mice of progeria, a milestone for gene therapy, according to a paper published by a team of US researchers in the journal Nature.

Francis Collins, director of the US National Institutes of Health, has teamed up with Harvard professor David Liu and others to tackle progeria.

The achievement, which was successfully tested in mice, was made possible by Liu's invention of a second-generation CRISPR gene-editing technique known as "base editing." With this, researchers may eventually be able to correct lifelong human genetic diseases, including progeria.

A rare but devastating disease

Francis Collins, the former head of the Human Genome Project, had been studying progeria for years before his breakthrough.

In 2003, Collins's lab discovered that progeria was caused by a mutation (think of it as a "typo") in a gene that encodes a protein called Lamin A. Lamin A plays a structural role in the nucleus.

Many people have mutations in various genes, but since people usually have two copies (one from their mother and one from their father), they tend to have at least one good copy, which is usually enough.

But the progeria mutation in Lamin A is different. While a good copy may exist, a mutated copy creates a toxic product that messes things up like a spanner in the works. This type of mutation is called a "dominant negative mutation."

The ideal solution would be to use CRISPR to specifically correct mutated copies. With this gene-editing tool, scientists can aim a pair of molecular "scissors" at any part of the genome, or DNA. Unfortunately, the first generation of CRISPR technology, while good at cutting genes, did not have the surgical precision or efficiency needed to correct the Lamin A mutation.

Complications of extensive cell editing

CRISPR scissors are good at finding targets and making cuts, but then the reconstructive surgery is left to cells, and there's no guarantee that every cell can do it.

In the lab, researchers can usually correct a few cells by growing them in a dish before further study.

But in humans, we need to correct most, if not all, cells accurately. It makes no sense to correct a progeria mutation in five cells of a patient's finger while leaving the rest of the body unrepaired.

This is where David Liu's work on the "base editor" is crucial. Liu identified the limitations of CRISPR technology early on and set out to develop molecular machines that could do more than just serve as targeted molecular scissors. He started with naturally occurring enzymes that change one chemical basis of the genetic code into another; For example, enzymes that can convert A(adenine) to G(guanine) or C(cytosine) to T(thymine).

The double-helical shape of DNA is supported by alternating sugar-phosphorus backbones (on both sides). Attached to the skeleton of each sugar is one of four chemical bases: adenine (A), thymine (T), guanine (G), and cytosine (C). The order of these bases determines the genetic code of an organism. In the above

Liu then modified the enzymes to make them more precise and fused them into CRISPR to create the fusion protein known as the "base editor." Because CRISPR technology is good at reading DNA and finding targets, it can efficiently deliver editors to genes that need to be altered.

It's worth emphasizing that Liu intentionally developed base editors so that they can change letters but no longer cut through DNA like CRISPR scissors. This is crucial because cutting DNA increases the risk of greater chromosomal deletions, which can damage cells.

Collins, Liu and their colleagues knew that they would have to implant the base editor into all (or at least most) of the cells of a mouse with progeria to cure it. To do so, they use hollowed out viruses as delivery vehicles.

They used a vector based on adeno-associated virus (AAV) because it is one of the smallest viruses and does not cause any known disease. Collins and Liu packaged AAV virions with genes encoding the relevant base-editing enzymes and injected them into mice. The treated mice largely avoided disease and became indistinguishable from healthy mice.

智能推荐

AI+医学影像 | 利用AI检测多发性硬化症患者的脑成像变化

2022-08-08伦敦大学学院和伦敦国王学院的研究人员开发了一种新的基于人工智能的方法,用于检测大脑对多发性硬化症(MS)治疗的反应。

涉及学科涉及领域研究方向创新开发“迷你”CRISPR基因组编辑系统

2022-08-17生物工程师们改造了一个“不能工作”的CRISPR系统,制造了一个更小版本的基因组工程工具。它小巧的体积使它更容易被输送到人类细胞、组织和身体进行基因治疗。

涉及学科涉及领域研究方向计算机图像分析确定了使人衰弱的肺部疾病的新亚型

2022-08-01伦敦大学学院的科学家们使用基于计算机的成像分析来识别特发性肺纤维化(IPF)患者肺部损伤的新模式,为一种以前未知的、限制生命的肺部疾病亚型提供了第一个证据。

涉及学科涉及领域研究方向肿瘤学创新 | 创新开发“治疗种子”可针对性地辐射肿瘤细胞

2022-11-11研究人员开发了一种新型、高度靶向和精确定位的放射疗法,它可以在保护脑癌患者健康组织的同时延缓肿瘤再生。

涉及学科涉及领域研究方向